I have a love-hate relationship with paper. I’ve never met a notebook, or a post-it note, or a planner I didn’t like. At the same time, I have no idea how to manage the mountains of paper that find their way into my home. Because my husband is efficient, process-minded, reasonable, and, above all, kind, he was helping me go through some papers last month. (As I type, it occurs to me that helping me go through paper may have as much to do with survival as with kindness. Our problems—paper and otherwise—always ooze out onto those we share life with, which is reason enough to keep fighting the good fight against those things that make us less than lovely to share a life with.)

I digress.

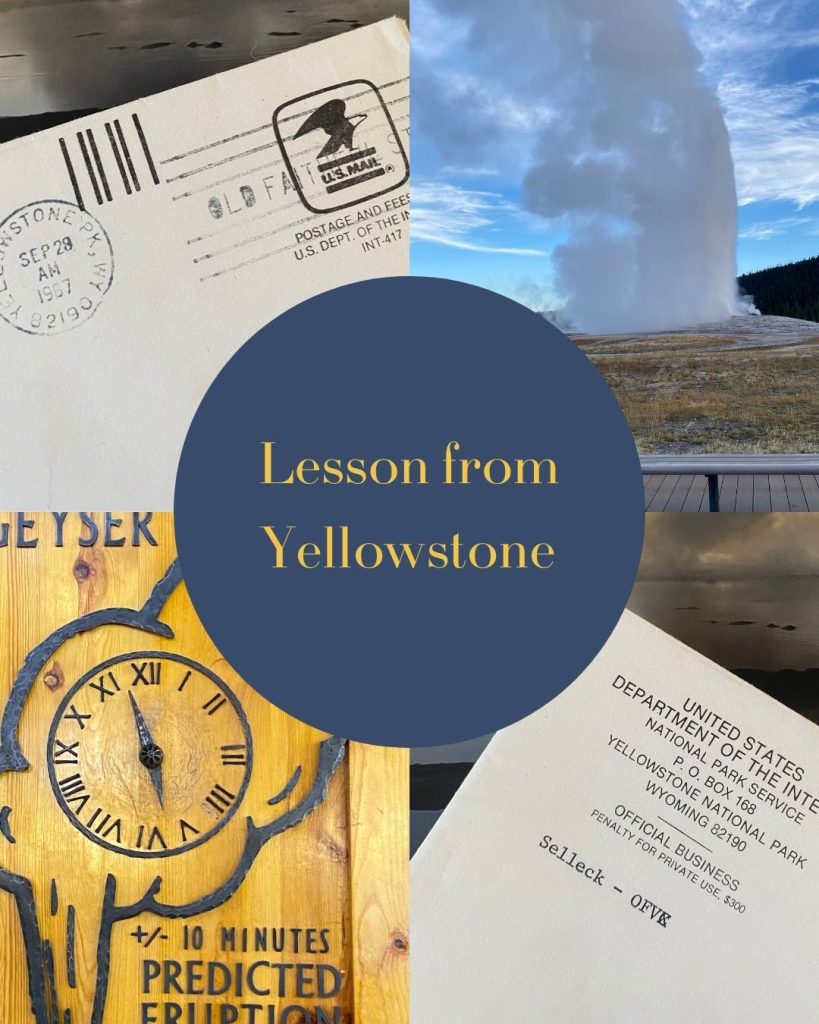

Among the unearthed pieces of paper, I discovered an envelope from the United States Department of the Interior. Postmarked September 1988, the month after I finished working in Yellowstone, it was a letter from one Ranger Selleck. He was my supervisor back in my days of volunteering at the Old Faithful Visitor Center information desk and, as I recall, had a mustache to match the Selleck name. A combination thank-you-for-your-service/letter of recommendation, it contained a long list of responsibilities I carried out during my time at the VC, including:

- the “highly diverse and challenging” task of answering visitors’ questions

- issuing fishing permits, Golden Age and Golden Access Passports

- observing Old Faithful Geyser’s eruptions and predicting the time of the next eruption based on those observations (Predictions always included a window of plus or minus 10 minutes. This was not due so much to the potential for human error but because Old Faithful’s activities are predicted based only on what we see above the surface, not on the unseen factors going on below.)

- monitoring the park radio, recording road conditions updates and weather reports

It was an accurate list and a fun trip down memory lane. Even more, reading it with nearly four additional decades of living behind me and an appreciation for lessons from Yellowstone, I recognized the significance of a single sentence that had been lost on me as a young adult. Your desire to get involved in our operation was most helpful as you basically trained yourself through observation and then put these skills to use.

Isn’t that what we do all the way through life–learning by observation and copying what we see?

We pay attention. We train ourselves, as Ranger Selleck said. And then we put those skills to use as best we can.

Beginning in our infancy, this is how we learn to walk and talk and get along with others. Over and over, through every one of Shakespeare’s seven stages, we’re busy watching and walking it out.

Sometimes we get the benefit of specific teaching. In Yellowstone, not understanding the weight of the wilderness is dangerous. Because of that, I was coached on how to talk to would-be campers as I issued backcountry camping permits. After all, they might be beginners, too. And given the sheer volume of humanity surging about in harmony with that prediction, it wasn’t something any of us took lightly—and the patient education I received from the rangers reflected that. Even though I received good teaching and did a credible job of training myself, I occasionally found myself out of my depth and learned by asking someone more experienced what to do.

Being a beginner is never easy. It’s awkward and humbling and in every way uncomfortable.

I know this now, in middle age, in ways I didn’t see at eighteen. Back then we were all beginners, or close to it. Some of us might have been naturally better at some things than others, but we were all just starting out.

When we’re young, we’re given mentors in the form of parents, older siblings, teachers, and coaches. When we’re new at something, whether on the job or at home, we’re encouraged to seek out mentors who can show us the way.

But then our kids grow up.

Our parents get older.

And, somehow, so do we.

Suddenly, the pool of resources we’ve been drawing from shrinks.

Not only are there fewer guides available, but the ones we’ve relied on are unable—or no longer here—to show us the way. And, besides, asking someone how to age well seems, well, insensitive at best.

Even so, we can watch. We can ask. We can put those lessons into practice. It was true for me as a beginning volunteer ranger, and it’s true in everyday life. This is why Yellowstone and other wild places matter. They give us more than novel experiences and happy memories. Though it teaches quietly, lessons from Yellowstone can shape our lives.

take heart & happy trails ~ Natalie🥾

🌄 Want more Lessons from Yellowstone? Sign up for Field Notes and uncover a new insight from Yellowstone every month.

Pin this ->